1818-1855 Arctic Medal

British Arctic Medal (1818-1855)

The first ever British polar medal, the Arctic Medal 1818-1855, was established by Queen Victoria, as noted in The London Gazette of January 30, 1857. It was granted to all persons, regardless of rank or class, who engaged in expeditions to the Arctic region, whether for discovery or search and rescue (including the abortive searches for the members of the 1845-48 Franklin Expedition), between 1818 and 1855. The medal was also awarded posthumously.

The initial awards were made in 1857. It is estimated that there were 2,500 eligible recipients. Total medals awarded however were only 1,486, of which 1,106 were awarded to members of the Royal Navy. The medal was also awarded to certain French and U.S. Navy personnel, members of the Hudson Bay Company, civilian support personnel and scientists.

The obverse of the 46mm X 33mm, silver, octagonal medal with milled edges, features the effigy of Queen Victoria and the text VICTORIA REGINA on either side. The reverse depicts an icebound ship with a sledge party in the foreground and the curved inscription, FOR ARCTIC DISCOVERIES, around the upper edge, and 1818-1855 in the exergue. The medal is suspended from a five-pointed star and fragile loop attachment (many examples now show repair) for the 65mm X 33mm white silk ribbon.

Expeditions, which appear to qualify for the Arctic Medal 1818-1855, include:

1818: Scotsman Sir John Ross, a British Navy officer in command of the HMS Isabel, was dispatched by the British Admiralty to explore Baffin Bay in search of the Northwest Passage. Sir William Parry commanded the brig, Alexander, as second-in-command of the expedition. Finding no passage, Ross turned for home before winter arrived. It proved a very unpopular decision.

1818: Scottish Royal Naval Officer David Buchan led the Spitzbergen Expedition north of the Spitsbergen Islands, but was forced back by heavy ice at 80° 34'N latitude. No European had ever reached this latitude except for William Scoresby, an Arctic whaler and scientist. In 1806, he reached 81° 30'N latitude. His ships were the HMS Dorothea and the HMS Trent, captained by John Franklin.

1819-22: Sir John Franklin, who was a member of the earlier 1818 Buchan Expedition, led the Coppermine Expedition, which completed a successful survey of the Arctic coastline from the Coppermine River to Point Turnagain, discovering Prudhoe Bay. By almost any objective standard, the expedition had been a disaster. Franklin had travelled 5,500 miles overland only to map a relatively small portion of coastline. He lost 11 of his 19-man overland expedition to starvation and exhaustion, including at least one murder and suggestions of cannibalism.

1819-20: Sir William Parry, second-in-command of the 1818 Ross Expedition, returned in command of two ships, Hecla and the Griper under command of Matthew Liddon. The expedition managed to sail past 110° W, further west than any prior expedition. Their voyage took them through Parry Channel, three quarters of the way across the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. It was the most productive voyage in the quest for the Northwest Passage until McClure's 1850-54 expedition.

1821-23: William Perry and G. F. Lyon sailed the Hecla and Fury, respectively, in search of the Northwest Passage via Hudson Bay. They reached the northern entrance to Foxe Channel, which separates the Foxe Basin from Hudson Bay and the Hudson Strait.

1822: Sir William Scoresby journeyed to east Greenland near the mouth of the fjord system, later named Scoresby Sound. The voyage of 1822 surveyed and charted with remarkable accuracy 400 miles of Greenland's east coast, between 69° 30'N and 72° 30'N, contributing to the first real and important geographic knowledge of East Greenland.

1823: Douglas Clavering and Edward Sabine explored northeast Greenland and made contact with the Inuit people. The expedition reached 80° 20'N latitude north of Spitzbergen. It discovered Shannon Island, Greenland at 75° 32'N latitude.

1824: G. F. Lyon sailed the Griper to survey the mainland coast from the west shore of Melville Peninsula to Point Turnagain, eventually turning back at Roe's Welcome Sound. Damaged by a storm during September 1924 near Cape Fullerton, and further damaged by a series of accidents and misfortunes, the Griper returned home during the fall of 1824.

1824-25: William E. Parry and Henry P. Hoppner sailed onboard the HMS Hecla and HMS Fury, respectively, seeking to find the Northwest Passage via Prince Regent Inlet. In late July 1825 the two ships freed themselves from ice, but 60 miles further south the Fury was driven against the western shore by wind and ice and was eventually lost at a site called Fury Beach.

1825-27: The Royal Navy's Mackenzie River Expedition was led by John Franklin and John Richardson. It mapped more than 600 miles of the Arctic coast. They explored the coast from the Coppermine River to Prudhoe Bay.

1826-28: Frederick William Beechey, in command of HMS Blossom, sailed with the goal of meeting Franklin and exploring the Bering Strait. During the summers of 1826 and 1827, Beechey explored the coast of Alaska from Kotzebue Sound to Point Barrow. During the winters of 1826 and 1827, the Blossom departed the Arctic and visited and extensively mapped San Francisco Bay.

1827: The Royal Navy Expedition led by William Parry, onboard the Hecla, reaches 82° 45'N in an attempt to achieve the North Pole. It would remain the highest latitude ever reached for 49 years.

1829-33: John Ross and James Clark Ross returned to the Arctic in charge of a private expedition onboard the Victory. The expedition would last an incredible four years. The expedition traveled further south through Prince Regent Inlet than any previous exploration. Most notably, the expedition discovered the site of the North Magnetic Pole. Eventually the expedition abandoned the Victory, which remained ice bound and traveled 300 miles overland to Fury Beach. They were eventually rescued by the whaler, Isabel.

1833-35: The Royal Navy Back River Expedition, led by George Back, was intended to search for the Ross Expedition of 1929-33. Back reached the mouth of the Back River at Chantrey Inlet and then unheroically, but wisely turned back before becoming icebound. Naturalist Richard King, who accompanied the expedition, contributed scientific information on meteorology and botany.

1836-37: George Back attempts to reach the Boothia Peninsula, but his ship, HMS Terror, is trapped in the ice at Southampton Island. He surveys the mainland from Wager Bay to Hecla Strait and westward to Point Turnagain. His vessel was badly damaged by offshore ice on the return voyage and eventually it was beached at Lough Swilly, Ireland.

1845: Franklin was recalled to lead one final expedition to traverse and map the Northwest Passage with the HMS Terror and Erebus, with a crew of 24 officers and 110 men. At Whale Fish Bay, Greenland, five of his men were discharged and sent home on the steam-frigate Rattler and the supply ship Barretto Junior due to sickness. The expedition's ships became icebound at Victoria Strait near King William Island on September 12, 1846 and would remain held fast by the ice for three winters. On April 22, 1848, the 105-man surviving crew members (Franklin, eight other officers, and 15 crewmen had already perished) set out for Back's Fish River (now Back River) and the Canadian mainland. The fate of the crew would remain a mystery for 14 years. The fate of Erebus and Terror would remain a mystery until 2014 and 2016, respectively.

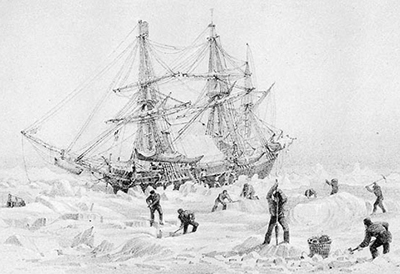

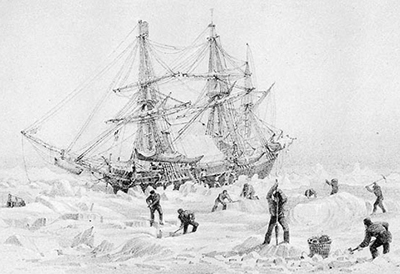

Drawing of HMS Terror Icebound (PD Art)

1848: Sir John Richardson and John Rae (Rae-Richardson Arctic Expedition) searched for Franklin. Led overland by John Richardson and John Rae, the party explored the accessible areas along Franklin's proposed route near the Mackenzie and Coppermine Rivers. Rae later interviewed the Inuit of the region and learned credible accounts of Franklin's desperate party resorting to cannibalism. This revelation was so unpopular back at home that Rae was shunned by both the British Admiralty as well as popular opinion. 1849: Sir Henry Kellett sailed onboard the HMS Herald through the Bering Strait, across the Chukchi Sea, and discovered Herald Island while searching for Franklin. 1850-54: The Robert McClure Arctic Expedition, onboard the HMS Investigator, joined the search for Franklin, spending three years icebound. McClure is credited with being the first man to discover and navigate the Northwest Passage across the Canadian Arctic, although much of the journey was over ice on sledges rather than water. The icebound Investigator was eventually lost to the Arctic and its crew, divided into three sledge parties, eventually reached the HMS North Star safely.

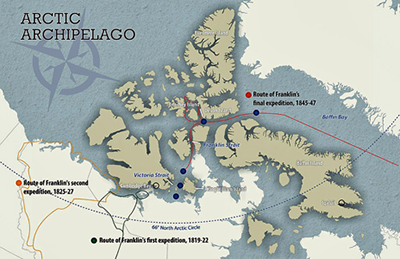

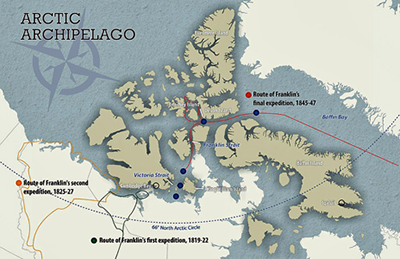

Routes of Franklin's Expeditions

1850: Ross led his final journey to the Arctic in search of the lost Franklin Expedition onboard the private vessel, Felix. The ship was not particularly well suited for Arctic exploration and Ross was required to frequently seek assistance from other ships. During October 1851, the Felix turned for home traveling along the Greenland coast, where Ross encountered stories (generally discarded) of the demise of Franklin and his entire party.

1851-54: Initially, McClure's Expedition included a second ship, the HMS Enterprise commanded by Richard Collinson. The two ships were separated during their journey to the Arctic. When he reached the Arctic, McClure decided to proceed on his own without the second ship. Arriving in the Arctic later than planned, the Enterprise was blocked by ice. After wintering over in Hong Kong, the Enterprise, returned the following season and carried out its own explorations. In August 1852, freed from the ice, Enterprise sailed along the south coast of Victoria Island into Coronation Gulf, the eastern most point reached by a ship from the Bering Strait. It was later revealed by John Rae that Enterprise had been just to the east of where the Franklin Expedition had been lost when it turned back for home.

1851: William Kennedy onboard the ketch, Prince Albert, searched for the lost Franklin Expedition. The expedition was sponsored by Jane Franklin. Kennedy's second-in-command was French Navy Sub-Lieutenant Joseph Rene Bellot. Although the expedition failed to locate Franklin, it did acquire significant knowledge of the flora, fauna and cartography of the area. Kennedy was selected to lead a second expedition in search of Franklin in 1853 onboard the Isabel, Jane Franklin's private steamer. Beset by problems, including the mutiny of the crew, the expedition never happened and Kennedy returned to England in 1855.

1852: Admiral Sir Edward Belcher led the largest British Naval Expedition and the last admiralty expedition to search for Franklin. Belcher was in command of five ships, Assistance, Resolute, Pioneer, Intrepid, and North Star. Upon arrival in the Arctic, Assistance and Resolute proceeded to different areas to search for Franklin. By 1854 with no results and worried about his icebound ships, Belcher ordered Kellett to abandon the Resolute and Intrepid and return to North Star by sledge. Aided by two ships, Phoenix and Breadalbane, Belcher returned to England where he faced court martial for losing his ship. He was exonerated, but his naval career was finished. In the interim, Resolute broke free of the ice and was taken as a prize by an American whaler. The ship was graciously returned to the British. The Resolute was decommissioned in 1879 and a competition was held to build a piece of furniture, which Queen Victoria could gift to the US president. The result was the Resolute Desk, which adorns the White House's Oval Office.

1852: Sir Edward Inglefield, onboard the Isabel, led a private expedition, funded by Jane Franklin, seeking information on the fate of the Franklin Expedition. Although the expedition failed to locate the Franklin Expedition, it did sail further into Smith Sound than any prior expedition. Jones Sound was also searched and when turning for home, Baffin Island's east coast was charted. French Navy, now full Lieutenant, Joseph Rene Bellot, was serving on his second Franklin Expedition rescue mission. In early 1852, while participating in an overland trek to deliver dispatches and supplies to Sir Edward Belcher, the ice shifted and he tragically disappeared into a crevasse near Wellington Channel.

1854: Dr. John Rae, who was now in-charge of the Mackenzie River District, surveyed Boothia Peninsula, on snowshoe, for the Hudson Bay Company. During his travels, he encountered Innuit at Repulse Bay. The Innuit told him of 35 to 40 white men dragging a boat, whose ships had been crushed by ice and were heading south to hunt deer. When the Innuit returned to the area the following year, they discovered 30 corpses and signs of cannibalism. They presented Rae with a small silver plate, engraved Sir John Franklin, K.C.H. This was the first indication of the Franklin Expedition's fate.

During the Arctic Medal's covered time frame (1818-1855), American merchant Henry Grinnell financed two arctic rescue expeditions. The First Grinnell Expedition (1850-51) was led by Edwin DeHaven with the ships USS Advance (often misidentified as the USS Arctic) and USS Rescue (often misidentified as the USS Release). The mission uncovered the graves of three Franklin crew members (John Torrington, John Hartnell and William Braine) on Beechey Island. The Second Grinnell Expedition (1853-55) was led by USN Medical Officer Elisha Kane onboard the USS Advance, searching for Franklin. The latter expedition explored Grinnell Land. These two Americans financed and equipped Arctic expeditions qualified for the 1818-1855 Arctic Medal as documented by the award of the medal to American crewman Walter Wilkerson, a crewmember onboard the USS Advance.

Between 1856 and 1875, numerous additional attempts to ascertain the fate of Franklin were undertaken by both British and American expeditions, but these all fell outside the award period requirement of 1818-1855. Among these were the Lady Franklin Expedition, led by Francis Leopold McClintock. During the summer of 1859, the sledge party, led by Lieutenant Hobson, located a document written by a member of the Franklin Expedition and concealed in a cairn on King William Island. It verified Franklin's death along with eight other officers and 15 crew members. It also established that the remaining survivors abandoned the two icebound ships and headed overland south toward the Back River.

HMS Terror Wreck and HMS Erebus Wreck (Parks Canada)

Note: During September 2014, almost 168 years after its loss, the Parks Canada Expedition, in collaboration with the Inuit, discovered the wreck of HMS Erebus in in Wilmot and Crampton Bay to the west of the Adelaide Peninsula just south of King William Island. The area had been identified by the Inuit. The area was approximately 60 miles from where most experts had assumed the wreck to be.

Two years later, the wreck of the HMS Terror was discovered along the southern coast of King William Island in the middle of Terror Bay. In 1992 the wrecks and the surrounding area were named a National Historic Site prior to their actual discovery.

Location of the Terror and Erebus

British Arctic Medal (1818-1855)

The first ever British polar medal, the Arctic Medal 1818-1855, was established by Queen Victoria, as noted in The London Gazette of January 30, 1857. It was granted to all persons, regardless of rank or class, who engaged in expeditions to the Arctic region, whether for discovery or search and rescue (including the abortive searches for the members of the 1845-48 Franklin Expedition), between 1818 and 1855. The medal was also awarded posthumously.

The initial awards were made in 1857. It is estimated that there were 2,500 eligible recipients. Total medals awarded however were only 1,486, of which 1,106 were awarded to members of the Royal Navy. The medal was also awarded to certain French and U.S. Navy personnel, members of the Hudson Bay Company, civilian support personnel and scientists.

The obverse of the 46mm X 33mm, silver, octagonal medal with milled edges, features the effigy of Queen Victoria and the text VICTORIA REGINA on either side. The reverse depicts an icebound ship with a sledge party in the foreground and the curved inscription, FOR ARCTIC DISCOVERIES, around the upper edge, and 1818-1855 in the exergue. The medal is suspended from a five-pointed star and fragile loop attachment (many examples now show repair) for the 65mm X 33mm white silk ribbon.

Expeditions, which appear to qualify for the Arctic Medal 1818-1855, include:

1818: Scotsman Sir John Ross, a British Navy officer in command of the HMS Isabel, was dispatched by the British Admiralty to explore Baffin Bay in search of the Northwest Passage. Sir William Parry commanded the brig, Alexander, as second-in-command of the expedition. Finding no passage, Ross turned for home before winter arrived. It proved a very unpopular decision.

1818: Scottish Royal Naval Officer David Buchan led the Spitzbergen Expedition north of the Spitsbergen Islands, but was forced back by heavy ice at 80° 34'N latitude. No European had ever reached this latitude except for William Scoresby, an Arctic whaler and scientist. In 1806, he reached 81° 30'N latitude. His ships were the HMS Dorothea and the HMS Trent, captained by John Franklin.

1819-22: Sir John Franklin, who was a member of the earlier 1818 Buchan Expedition, led the Coppermine Expedition, which completed a successful survey of the Arctic coastline from the Coppermine River to Point Turnagain, discovering Prudhoe Bay. By almost any objective standard, the expedition had been a disaster. Franklin had travelled 5,500 miles overland only to map a relatively small portion of coastline. He lost 11 of his 19-man overland expedition to starvation and exhaustion, including at least one murder and suggestions of cannibalism.

1819-20: Sir William Parry, second-in-command of the 1818 Ross Expedition, returned in command of two ships, Hecla and the Griper under command of Matthew Liddon. The expedition managed to sail past 110° W, further west than any prior expedition. Their voyage took them through Parry Channel, three quarters of the way across the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. It was the most productive voyage in the quest for the Northwest Passage until McClure's 1850-54 expedition.

1821-23: William Perry and G. F. Lyon sailed the Hecla and Fury, respectively, in search of the Northwest Passage via Hudson Bay. They reached the northern entrance to Foxe Channel, which separates the Foxe Basin from Hudson Bay and the Hudson Strait.

1822: Sir William Scoresby journeyed to east Greenland near the mouth of the fjord system, later named Scoresby Sound. The voyage of 1822 surveyed and charted with remarkable accuracy 400 miles of Greenland's east coast, between 69° 30'N and 72° 30'N, contributing to the first real and important geographic knowledge of East Greenland.

1823: Douglas Clavering and Edward Sabine explored northeast Greenland and made contact with the Inuit people. The expedition reached 80° 20'N latitude north of Spitzbergen. It discovered Shannon Island, Greenland at 75° 32'N latitude.

1824: G. F. Lyon sailed the Griper to survey the mainland coast from the west shore of Melville Peninsula to Point Turnagain, eventually turning back at Roe's Welcome Sound. Damaged by a storm during September 1924 near Cape Fullerton, and further damaged by a series of accidents and misfortunes, the Griper returned home during the fall of 1824.

1824-25: William E. Parry and Henry P. Hoppner sailed onboard the HMS Hecla and HMS Fury, respectively, seeking to find the Northwest Passage via Prince Regent Inlet. In late July 1825 the two ships freed themselves from ice, but 60 miles further south the Fury was driven against the western shore by wind and ice and was eventually lost at a site called Fury Beach.

1825-27: The Royal Navy's Mackenzie River Expedition was led by John Franklin and John Richardson. It mapped more than 600 miles of the Arctic coast. They explored the coast from the Coppermine River to Prudhoe Bay.

1826-28: Frederick William Beechey, in command of HMS Blossom, sailed with the goal of meeting Franklin and exploring the Bering Strait. During the summers of 1826 and 1827, Beechey explored the coast of Alaska from Kotzebue Sound to Point Barrow. During the winters of 1826 and 1827, the Blossom departed the Arctic and visited and extensively mapped San Francisco Bay.

1827: The Royal Navy Expedition led by William Parry, onboard the Hecla, reaches 82° 45'N in an attempt to achieve the North Pole. It would remain the highest latitude ever reached for 49 years.

1829-33: John Ross and James Clark Ross returned to the Arctic in charge of a private expedition onboard the Victory. The expedition would last an incredible four years. The expedition traveled further south through Prince Regent Inlet than any previous exploration. Most notably, the expedition discovered the site of the North Magnetic Pole. Eventually the expedition abandoned the Victory, which remained ice bound and traveled 300 miles overland to Fury Beach. They were eventually rescued by the whaler, Isabel.

1833-35: The Royal Navy Back River Expedition, led by George Back, was intended to search for the Ross Expedition of 1929-33. Back reached the mouth of the Back River at Chantrey Inlet and then unheroically, but wisely turned back before becoming icebound. Naturalist Richard King, who accompanied the expedition, contributed scientific information on meteorology and botany.

1836-37: George Back attempts to reach the Boothia Peninsula, but his ship, HMS Terror, is trapped in the ice at Southampton Island. He surveys the mainland from Wager Bay to Hecla Strait and westward to Point Turnagain. His vessel was badly damaged by offshore ice on the return voyage and eventually it was beached at Lough Swilly, Ireland.

1845: Franklin was recalled to lead one final expedition to traverse and map the Northwest Passage with the HMS Terror and Erebus, with a crew of 24 officers and 110 men. At Whale Fish Bay, Greenland, five of his men were discharged and sent home on the steam-frigate Rattler and the supply ship Barretto Junior due to sickness. The expedition's ships became icebound at Victoria Strait near King William Island on September 12, 1846 and would remain held fast by the ice for three winters. On April 22, 1848, the 105-man surviving crew members (Franklin, eight other officers, and 15 crewmen had already perished) set out for Back's Fish River (now Back River) and the Canadian mainland. The fate of the crew would remain a mystery for 14 years. The fate of Erebus and Terror would remain a mystery until 2014 and 2016, respectively.

Drawing of HMS Terror Icebound (PD Art)

1848: Sir John Richardson and John Rae (Rae-Richardson Arctic Expedition) searched for Franklin. Led overland by John Richardson and John Rae, the party explored the accessible areas along Franklin's proposed route near the Mackenzie and Coppermine Rivers. Rae later interviewed the Inuit of the region and learned credible accounts of Franklin's desperate party resorting to cannibalism. This revelation was so unpopular back at home that Rae was shunned by both the British Admiralty as well as popular opinion. 1849: Sir Henry Kellett sailed onboard the HMS Herald through the Bering Strait, across the Chukchi Sea, and discovered Herald Island while searching for Franklin. 1850-54: The Robert McClure Arctic Expedition, onboard the HMS Investigator, joined the search for Franklin, spending three years icebound. McClure is credited with being the first man to discover and navigate the Northwest Passage across the Canadian Arctic, although much of the journey was over ice on sledges rather than water. The icebound Investigator was eventually lost to the Arctic and its crew, divided into three sledge parties, eventually reached the HMS North Star safely.

Routes of Franklin's Expeditions

1850: Ross led his final journey to the Arctic in search of the lost Franklin Expedition onboard the private vessel, Felix. The ship was not particularly well suited for Arctic exploration and Ross was required to frequently seek assistance from other ships. During October 1851, the Felix turned for home traveling along the Greenland coast, where Ross encountered stories (generally discarded) of the demise of Franklin and his entire party.

1851-54: Initially, McClure's Expedition included a second ship, the HMS Enterprise commanded by Richard Collinson. The two ships were separated during their journey to the Arctic. When he reached the Arctic, McClure decided to proceed on his own without the second ship. Arriving in the Arctic later than planned, the Enterprise was blocked by ice. After wintering over in Hong Kong, the Enterprise, returned the following season and carried out its own explorations. In August 1852, freed from the ice, Enterprise sailed along the south coast of Victoria Island into Coronation Gulf, the eastern most point reached by a ship from the Bering Strait. It was later revealed by John Rae that Enterprise had been just to the east of where the Franklin Expedition had been lost when it turned back for home.

1851: William Kennedy onboard the ketch, Prince Albert, searched for the lost Franklin Expedition. The expedition was sponsored by Jane Franklin. Kennedy's second-in-command was French Navy Sub-Lieutenant Joseph Rene Bellot. Although the expedition failed to locate Franklin, it did acquire significant knowledge of the flora, fauna and cartography of the area. Kennedy was selected to lead a second expedition in search of Franklin in 1853 onboard the Isabel, Jane Franklin's private steamer. Beset by problems, including the mutiny of the crew, the expedition never happened and Kennedy returned to England in 1855.

1852: Admiral Sir Edward Belcher led the largest British Naval Expedition and the last admiralty expedition to search for Franklin. Belcher was in command of five ships, Assistance, Resolute, Pioneer, Intrepid, and North Star. Upon arrival in the Arctic, Assistance and Resolute proceeded to different areas to search for Franklin. By 1854 with no results and worried about his icebound ships, Belcher ordered Kellett to abandon the Resolute and Intrepid and return to North Star by sledge. Aided by two ships, Phoenix and Breadalbane, Belcher returned to England where he faced court martial for losing his ship. He was exonerated, but his naval career was finished. In the interim, Resolute broke free of the ice and was taken as a prize by an American whaler. The ship was graciously returned to the British. The Resolute was decommissioned in 1879 and a competition was held to build a piece of furniture, which Queen Victoria could gift to the US president. The result was the Resolute Desk, which adorns the White House's Oval Office.

1852: Sir Edward Inglefield, onboard the Isabel, led a private expedition, funded by Jane Franklin, seeking information on the fate of the Franklin Expedition. Although the expedition failed to locate the Franklin Expedition, it did sail further into Smith Sound than any prior expedition. Jones Sound was also searched and when turning for home, Baffin Island's east coast was charted. French Navy, now full Lieutenant, Joseph Rene Bellot, was serving on his second Franklin Expedition rescue mission. In early 1852, while participating in an overland trek to deliver dispatches and supplies to Sir Edward Belcher, the ice shifted and he tragically disappeared into a crevasse near Wellington Channel.

1854: Dr. John Rae, who was now in-charge of the Mackenzie River District, surveyed Boothia Peninsula, on snowshoe, for the Hudson Bay Company. During his travels, he encountered Innuit at Repulse Bay. The Innuit told him of 35 to 40 white men dragging a boat, whose ships had been crushed by ice and were heading south to hunt deer. When the Innuit returned to the area the following year, they discovered 30 corpses and signs of cannibalism. They presented Rae with a small silver plate, engraved Sir John Franklin, K.C.H. This was the first indication of the Franklin Expedition's fate.

During the Arctic Medal's covered time frame (1818-1855), American merchant Henry Grinnell financed two arctic rescue expeditions. The First Grinnell Expedition (1850-51) was led by Edwin DeHaven with the ships USS Advance (often misidentified as the USS Arctic) and USS Rescue (often misidentified as the USS Release). The mission uncovered the graves of three Franklin crew members (John Torrington, John Hartnell and William Braine) on Beechey Island. The Second Grinnell Expedition (1853-55) was led by USN Medical Officer Elisha Kane onboard the USS Advance, searching for Franklin. The latter expedition explored Grinnell Land. These two Americans financed and equipped Arctic expeditions qualified for the 1818-1855 Arctic Medal as documented by the award of the medal to American crewman Walter Wilkerson, a crewmember onboard the USS Advance.

Between 1856 and 1875, numerous additional attempts to ascertain the fate of Franklin were undertaken by both British and American expeditions, but these all fell outside the award period requirement of 1818-1855. Among these were the Lady Franklin Expedition, led by Francis Leopold McClintock. During the summer of 1859, the sledge party, led by Lieutenant Hobson, located a document written by a member of the Franklin Expedition and concealed in a cairn on King William Island. It verified Franklin's death along with eight other officers and 15 crew members. It also established that the remaining survivors abandoned the two icebound ships and headed overland south toward the Back River.

HMS Terror Wreck and HMS Erebus Wreck (Parks Canada)

Note: During September 2014, almost 168 years after its loss, the Parks Canada Expedition, in collaboration with the Inuit, discovered the wreck of HMS Erebus in in Wilmot and Crampton Bay to the west of the Adelaide Peninsula just south of King William Island. The area had been identified by the Inuit. The area was approximately 60 miles from where most experts had assumed the wreck to be.

Two years later, the wreck of the HMS Terror was discovered along the southern coast of King William Island in the middle of Terror Bay. In 1992 the wrecks and the surrounding area were named a National Historic Site prior to their actual discovery.

Location of the Terror and Erebus

Website Maintained by Keith Emroll